Here’s an example of breaking down player tendencies and how it can help your defense take away players’ strengths and take advantage of their weaknesses.

OF COURSE, your defensive philosophy contributes to how you are guarding ANYBODY. Some coaches have a system of guarding every player the same way (never giving up middle drives in certain defensive systems - aka NO MIDDLE or FORCING BASELINE when the offense has the ball in particular positions of the floor).

Some programs will guard players different ways based on what they’re good at and what they’re bad at. Put another way, they want to take away the things opponents prefer to do to while forcing them to do things they don’t like or just aren’t very good at.

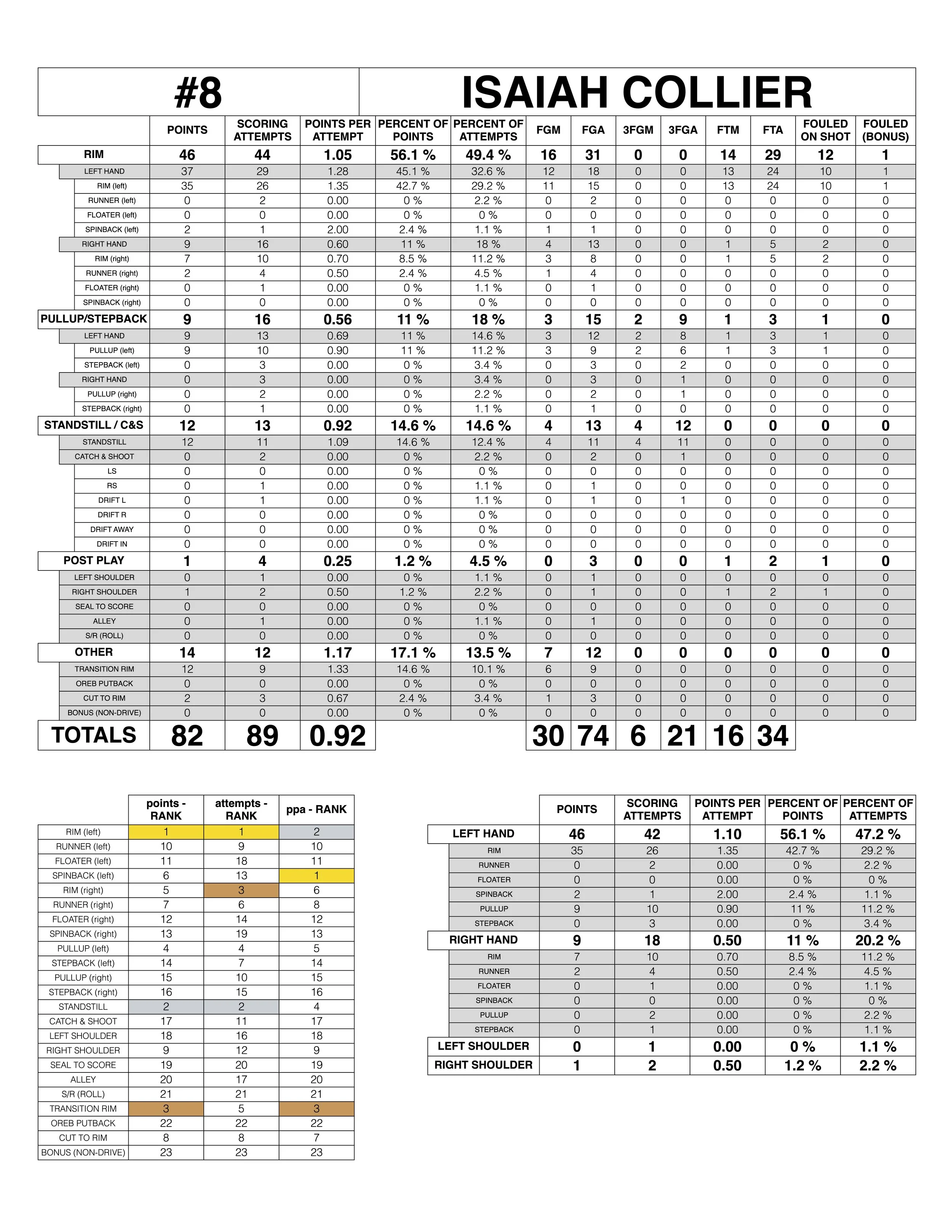

This first example is a breakdown of Utah Jazz point guard Isaiah Collier and comes from the Utah Jazz Summer League schedule during the summer of 2025. Collier played in 7 of the 8 games Utah played during Summer League, so this data set comes from those seven games.

The picture above is a look at the overall breakdown we produce after chopping up game film to help determine how to guard an individual. There’s a lot of numbers here that might mean different things to different people. I’ll touch on what I look at and what jumps out to me.

The first place I look here is the POINTS column. I really want to know two things: (1) HOW DOES THIS PLAYER SCORE POINTS? and (2) WHERE DOES THIS PLAYER SCORE POINTS? It’s clear just glancing at the numbers above that #8 Isaiah Collier scores most of his points AT THE RIM. 46 of his 82 points came at the rim.

The next place I go from here is: WHAT HAND DOES HE SCORE BEST TO? Again, it’s clear looking at the numbers that this particular player CLEARLY prefers scoring to his LEFT HAND. Of the 46 points he scored at the rim, 37 of them came as a result of DRIVES TO THE LEFT.

From here I take a look at his PULLUP GAME. It’s clear looking at Collier that HE ALSO PREFERS PULLING UP TO HIS LEFT - and he’s had more success at it. If you look at the small table in the bottom right-hand corner of the above chart, we’re taking a look at EVERYTHING a player does to his RIGHT or his LEFT, including pull-up jumpers and setback jumpers. In Collier’s case, he didn’t make a single pull-up or setback to his right hand. He scored some getting to the RIM with his right hand, but he didn’t have the same success he had getting to the rim with his left hand (0.7 points per attempt going to the rim with his right hand compared to 1.35 points per attempt going to the rim with his left hand).

In Collier’s case, it would be clear to me that we want to STOP HIM FROM DRIVING LEFT. We’re not as concerned with him hurting us to his RIGHT. Of course, this is a professional basketball player, so to say he’s not capable of hurting you to his right is an obvious point. But if you wanted to gain an advantage guarding this player - it’s clear to me that you gain an advantage by KEEPING HIM OFF HIS LEFT HAND in this particular case.

Let’s take a look at the data in a different way - a table that makes these things a little easier to see at first glance.

Looking at the top table (SORTED BY POINTS SCORED) you can see the same thing we talked about before. Pretty simple, right? He scores most of his points by getting to the rim with his left hand.

If you continue down that top chart line-by-line you see the SECOND-most points he scored came from simple STANDSTILL shots (this includes both 2s and 3s - although in my experience these days it’s rare for players to accumulate a large number of STANDSTILL 2s, the exception being a player who is getting touches in the mid-post area who likes to face-up and go to work. In those cases you might see more, but it tends to be a small amount of attempts).

SIDEBAR - STANDSTILL 3s and CATCH & SHOOT 3s - You’ll see upon examination that I combine these numbers in the top chart (the first picture in this article). Just about all these numbers in the first chart will be 3s, but you can see that Collier did shoot one CATCH & SHOOT 2… If you’re like me, the first thing you want to make clear is: What is the different between a standstill 3 and a catch & shoot 3? For me, a STANDSTILL 3 is a shot where there isn’t movement leading into the shot. It can be a bit subjective sometimes, but It’s basically a STANDING STILL, RHYTHM SHOT. If a player is moving to the left or right or drifting one way or another and then CATCHES & SHOOTS the ball off of that movement, I consider it catch & shoot. Again, this can be subjective in a number of occasions - and I’d be happy to go into a more detailed breakdown of what those look like - but that’s for another discussion.

Overall, guarding this player would be a relatively simple approach. He has a clear preference to his left, the numbers show it, and he is better at driving to his left. So we would limit his chances of doing so by labeling him a NO LEFT guy.

ANOTHER SIDEBAR - ASSISTS AND TURNOVERS - In a more detailed analysis of players and how they positively or negatively influence the game, it’s important to take a look at what certain players do driving to their left and driving to their right with ASSISTS and TURNOVERS. I haven’t even looked at the numbers yet (and I’ll do so in a second when I finish this paragraph), but I’d be willing to bet that Collier has more success with ASSISTS driving to his LEFT. I’d also be willing to bet that Collier runs into more trouble with TURNOVERS when he drives to his RIGHT. Let’s take a look at that hypothesis.

These numbers would support my hypothesis. And this could spawn an entirely different conversation about how to guard certain players who are more of distributor-type players with the ball in their hand. BUT, as a general rule, I wouldn’t game-plan as much for how a player could help get other people points (assists). That’s a general rule. I would plan first and foremost on how an individual players scores points. Either way - when you look at the overall numbers, it’s clear that Collier drives LEFT much more than he drives RIGHT. And for as few times as he attacked to his right compared to his left, he gets himself into trouble much more when he goes RIGHT. So the approach of keeping him OFF HIS LEFT and living with what happens when he is attacking to his RIGHT would hold up here.

ADDITIONAL SIDEBAR ABOUT LEFT / RIGHT ASSISTS AND TURNOVERS - When I personally scout opponents, I chart out EVERY SINGLE THING a player does when attacking with the ball. Even a simple drive and kick that leads to nothing - if a player attacks at all with the ball, I chart it. This gives you an even BETTER feel for the hand a player prefers to attack with. This detailed analysis is NOT included in the pictures above (if you noticed, the ASSISTS/TURNOVERS - RIGHT HAND/LEFT HAND breakdown above isn’t either). In the picture below, you can see a more in-depth example of this kind of analysis that I used in a scout versus BYU and lottery pick Egor Denim (#8 pick in the 2025 NBA Draft) during the 24-25 season when I was an assistant at the University of Utah.

It was rare to show these breakdowns to our team, but in this case we did. I felt it would make an impression on the players to see the difference in numbers and hammer home the importance of keeping him off his left hand. It was an important factor in that game, which we won. It’s also rare to try keeping a LOTTERY PICK off of one hand, but in this case I thought it was a no-brainer. This is where that extra detail of NON-SHOOTING drives made all the difference.

In the chart above, when you look at LEFT HAND (66) compared to RIGHT HAND (18), there’s a staggering difference. But this number includes NON-SHOOTING drives. The differences would still be “staggering” if you take NON-SHOOTING out of the equation, but it wouldn’t stand out quite the same way. Taking NON-SHOOTING out of the equation would make 22 scoring attempts to the left compared to 5 to the right.

This scout was done over the first 5 games of BIG 12 play, which I think is a very good indicator of a player’s overall tendencies. Obviously, the more games you chart, the more the numbers will show overall tendencies. But another thing to consider in scouting is this: It’s important to see how a player is performing and what his tendencies are RIGHT NOW. If you were to go back 20 games and chart things out over that long of a span, numbers may look different.

Case in point: after we used this NO LEFT strategy in our first matchup against BYU and Denim, other teams started to take notice. People started taking away his left hand more. As a result, and to Denim’s credit, he made adjustments and ended up getting much better attacking to his right. As a result, his numbers looked much different near the end of the season. See the chart below.

See what a difference an entire season can make? Denim’s first set of numbers were from the first five BIG 12 games of the season. Our last matchup with BYU was the final regular season BIG 12 game of the year, so these numbers were from much later in the year. How can these numbers be so different? Maybe people were forcing him right more - that’s certainly one reason. Denim was also a freshman, and freshmen get better throughout the season. It’s probably a combination of both. Players start to figure things out when people start guarding them different ways and they make adjustments and improvements. Denim clearly got better throughout the year attacking to his right hand. My guess is that early on and throughout non-conference play, this freshman (and all freshmen as a general rule) are going to do the things they’re most comfortable with.